Shell Righting

When a gastropod shell is overturned so that the aperture is dorsal, the snail will initially withdraw into the shell but then eventually attempts to turn itself over or “right” itself (Berg 1974). The way in which strombids “right” themselves differs to that of other snails. The majority of snails will extend their foot over their shell and pull themselves over onto their ventral surface. In contrast, strombids gain a purchase by inserting their sharp operculum under their shell and then quickly jerking the shell over with a “kick” (Berg 1974). By withdrawing into the shell the strombid covers the aperture of the shell with its operculum and then slowly unfolds the foot. The eyes are then able to protrude from the aperture and point upwards with the tentacles on the eyestalks moving slightly. All Strombus species display the quick kicking motion described earlier and if a purchase is obtained on the substrate then the shell is turned dorsal side up (Berg 1974). Juvenile snails right their shells by pulling with the propodium, and do not `kick' at the substratum until the expanded outer lip of the adult shell has formed (Perron 1978).

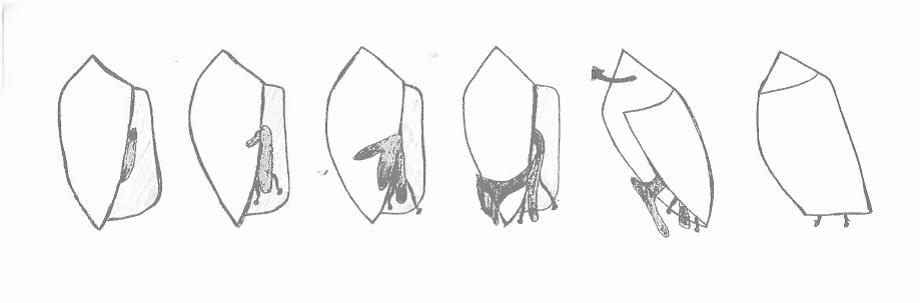

Figure 1. Diagram of the common steps in the shell righting behaviour of strombids (adapted from Berg, 1974).

Incomplete "intention" movements towards the parietal wall are performed in some instances (Berg 1975) and these can occur through the stromboid notch or over the parietal lip of the shell and prolong the righting period (Berg 1974). The snails often make slight movements with the metapodium in the direction of the area of the shell over which they are about to extend. These are labelled "intention movements", because the snail extends over that area soon after making these slight incomplete movements. The movements may just be a quick, short (1cm) jerk, or a slower partial extension over the shell. The foot usually moves back to its ready position between intention movements, although it may remain partially extended. Intention movements are well known in other animal groups but have not heretofore been reported for molluscs (Berg 1974).

Image of Lentigo lentiginosus overturned with the eyes starting to emerge from the aperture prior to righting itself (Photographer: Asia Armstrong).

If the strombid has unsuccessful attempts at righting it will withdraw the foot to the ready position. With a greater number of attempts, the foot may not withdraw completely but remain slightly extended. The snail then makes additional intention movements or simply more attempts at righting. The operculum is placed in different areas around the edge of the shell if the first attempts are unsuccessful. The initial attempts are usually made to that side of the shell lying closest to the substratum and further attempts are made to the opposite side or through the most posterior area of the aperture. The movements used in righting differ slightly among the species, as do the mean number of attempts required to right, the time taken, the occurrence of intention movements, and the areas of placement of the operculum in repeated attempts (Berg 1974).

Video of shell righting behaviour of Lentigo lentiginosus (captured by Asia Armstrong).

An unbalanced centre of gravity closer to the aperture side of the shell helps to facilitate righting by making the upturned shell unstable (Savazzi 1991). Several strombid species, including Lentigo lentiginosus enhance this effect with the adaptation of one or more knobs on the dorsal surface of the last whorl of the shell. The presence of the knobs force the aperture of an overturned shell to lean toward either side and thus reduce the amount of shell rotation necessary for righting (Savazzi 1991).

|